Similar to friction stir welding or ultrasonic welding, PSW is not a conventional fusion welding process. Polymer Stir Welding, patented by royos joining solutions GmbH, Lieboch, Austria, is a modern welding process in the broader sense, developed primarily for joining thermoplastic polymers with metals. In contrast to conventional welding processes, in which metals or polymers are usually melted, the metal in the PSW process remains solid, while only the polymer is melted.

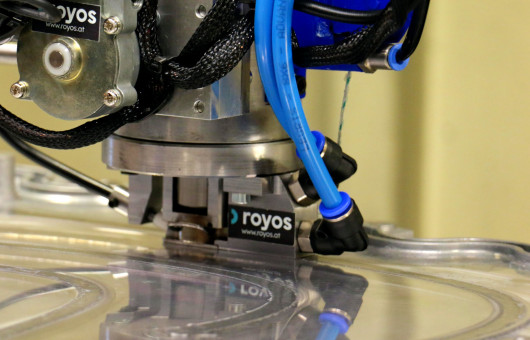

A heated, rotating tool pin is introduced into the joining zone between polymer and metal (Fig. 1). Local melting of the polymer occurs, while at the same time the pin generates mechanical surface structuring and undercuts in the metal. The molten polymer is pressed into these structures and solidifies there, creating a positive mechanical interlock between the two materials, which ensures a strong and durable joint (Fig. 2).

New opportunities for sustainable hybrid composites

When we think of lightweight construction, lightweight metals or polymers usually come to mind – but rarely the possibility of combining the advantages of both material worlds. Industry too is increasingly relying on a balanced material mix in order to achieve cost benefits, weight reduction, and, above all, to meet the targets or regulatory requirements for CO₂ reduction. In raw material production, polymers emit significantly less CO₂ than metals, especially for primary alloys – high-grade alloys as used in the automotive sector or aerospace. Their extraction is also less resource-intensive (keyword: bauxite mining for aluminium). Research is also focusing intensively on the production and industrial application of bio-based polymers made from plants and plant fibres, which are considered particularly environmentally friendly. Until now, the production of metal-polymer hybrid components was regarded as cost-intensive and labour-intensive. Injection moulding, adhesive bonding or screwing were the established methods.

For decades, the arguments have remained the same when it comes to creating durable joints between polymers and metals: Screwing increases weight and cycle time; adhesive bonding requires surface pretreatment, curing time, generates VOC emissions (volatile organic compounds) and significantly impairs recyclability. Designers accepted this Gordian knot of extra cost, process risk and ecological footprint because there was simply no alternative.

With PSW, for example, an injection-moulded PA66-GF30 component can be permanently joined in line takt with an aluminium tray – without pretreatment, adhesive or additional seals.

How PSW works – briefly explained

The PSW process combines three process steps that are necessary for achieving an optimum joint between metal and polymer. First, the metal is conditioned, i.e. cleaned, structured and preheated. At the same time, the polymer is melted and can penetrate into the newly created surface structure of the metal. Subsequently, the joining zone cools down, causing the polymer to solidify and form a particularly strong joint: the metal is only locally and slightly heated, so that no significant thermal stresses occur. Furthermore, no chips are released, and the fresh surface is directly sealed.

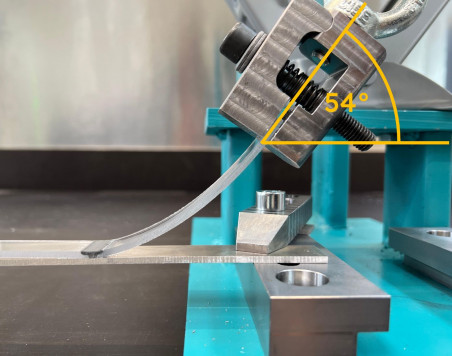

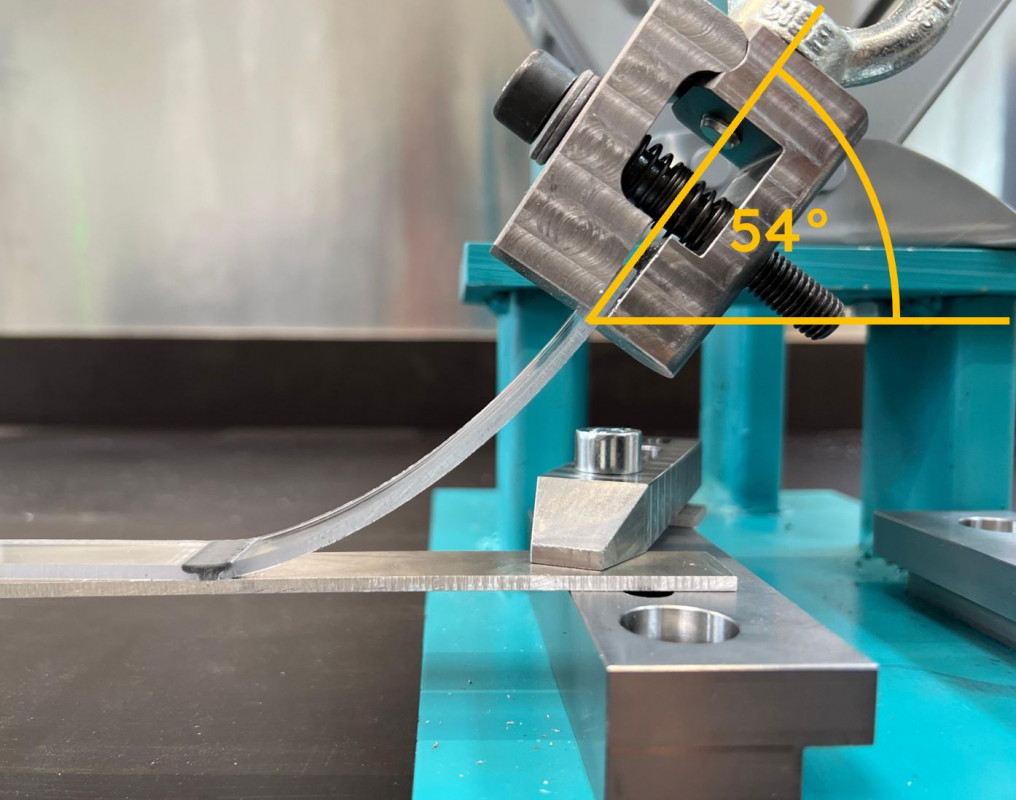

Since PSW operates with very low process forces of less than 2 kN, even very thin sheets or foils can be joined without visible distortion. The process force is required on the one hand to guide the stirring pin through the polymer onto the metal surface, and on the other hand to press the shoe against the polymer surface to prevent leakage of the molten polymer. By comparison, friction stir welding for the production of a cooling channel of a battery tray requires up to 10 kN of contact force. The lower forces make it possible to design components even lighter, as they only have to withstand low loads.

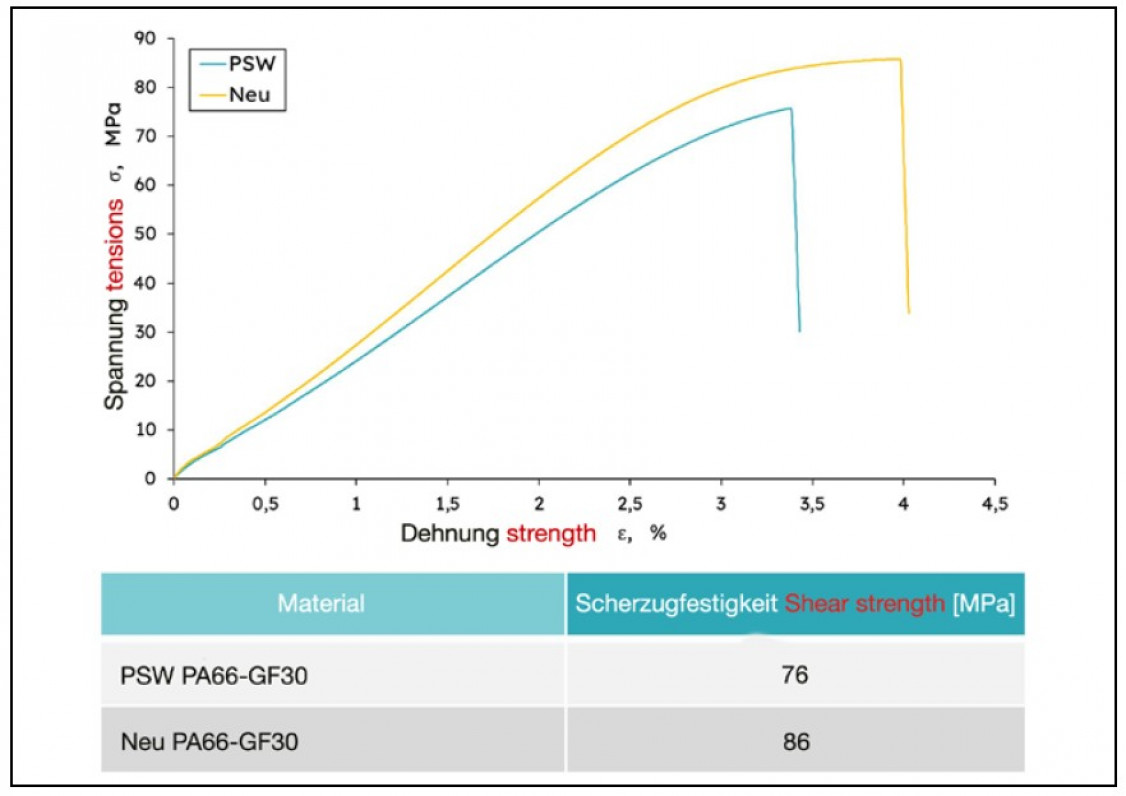

In combination with fibre-reinforced materials, another advantage of PSW comes into play: the fibre orientation in thermoplastic glass- or carbon-fibre reinforced polymers is largely preserved, so that the strength values are significantly higher than those of the joining methods used so far.

Weight down, strength up

Especially in the field of electromobility, next-generation batteries have achieved progress in terms of fire behaviour and operating temperature range, making polymers increasingly suitable as housing materials. The idea: the metal takes on the load-bearing functions, while the polymer realises the component functions such as protective casing, ribs, clips or media guides.

As a calculation based on a battery tray for a PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicle) shows, this approach using PSW joints can save up to 50 % in weight and reduce the CO₂ footprint by up to 80 %. For comparison: polyamide saves about 10 kg of CO₂ per 1 kg in direct comparison with aluminium [1].

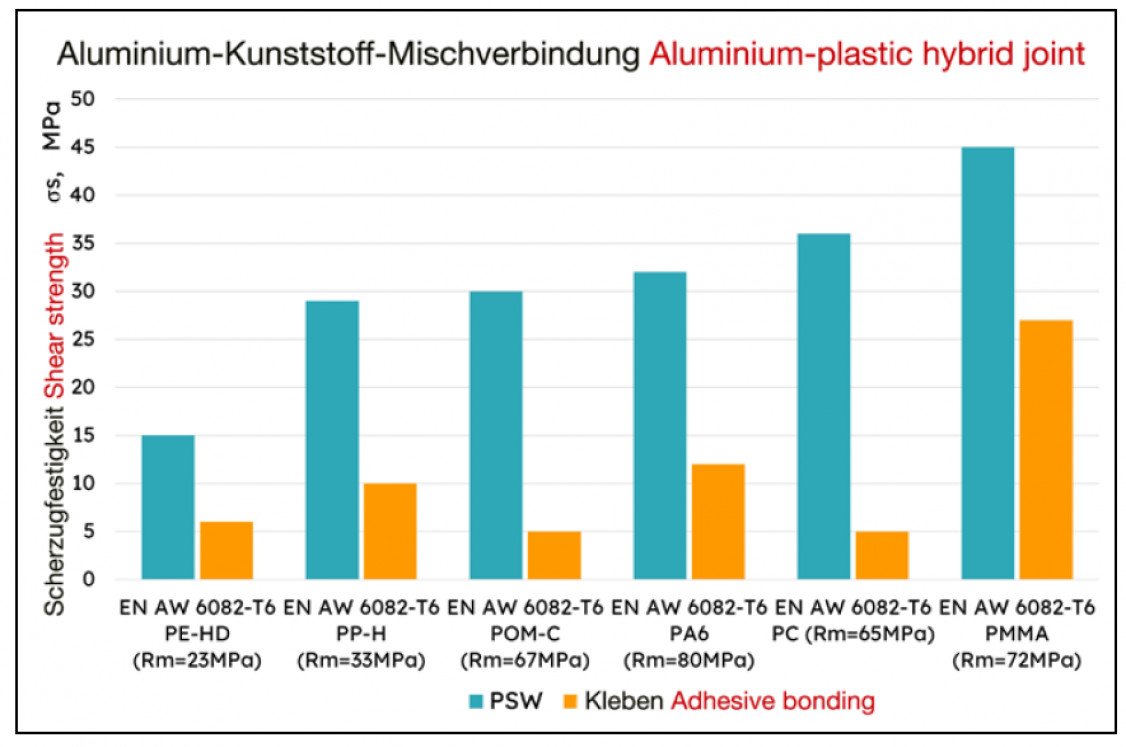

The same applies to the strengths of aluminium–polymer hybrid joints. Fig. 3 shows a direct comparison of the strength values of composites produced using the PSW process and those produced by adhesive bonding.

Economic efficiency: PSW and adhesive bonding compared

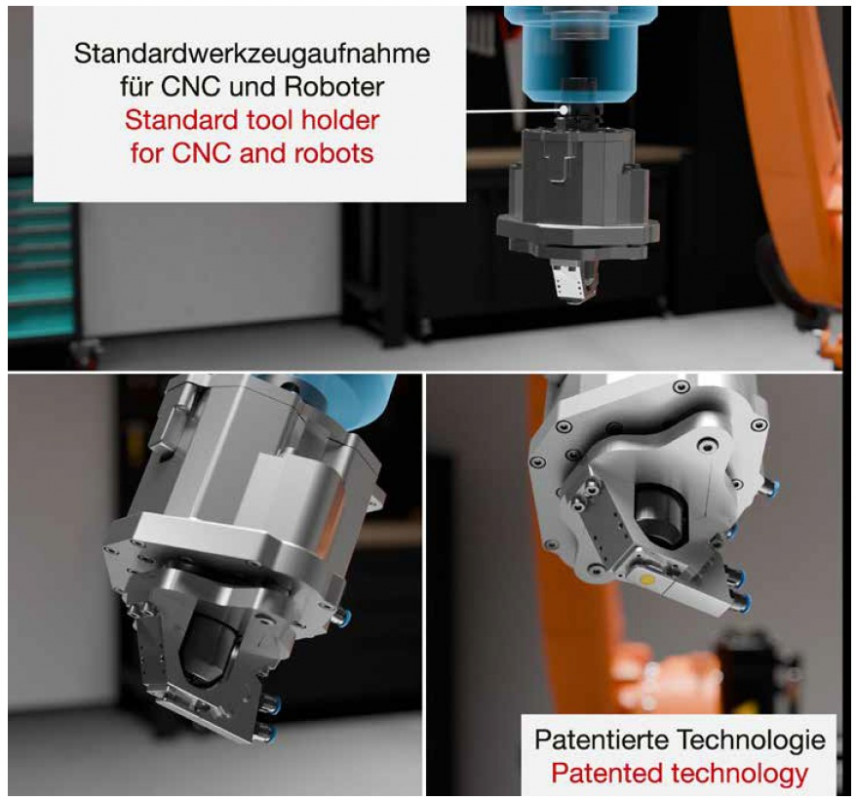

While adhesive joints require primers, dosing systems, exhaust systems for VOC emissions as well as grease- and silicone-free surfaces, PSW only requires a tool attachment that can be operated on standard 4-axis CNC machines or in robot cells. The cycle time for a 1000 mm long polymer-metal seam is around 60–80 s with PSW. By contrast, two-component adhesives can require curing times of up to 12 h.

A cost analysis based on an OEM component showed 75 % lower joining costs for an annual production volume of 250,000 units thanks to simplified joining technology, cheaper raw materials and efficient manufacturing methods. In addition, material substitution towards lighter materials brings further potential savings.

Joining different polymers

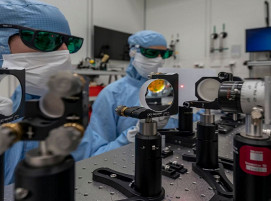

Originally developed for polymer–metal joints, PSW can now be used to weld a wide range of different polymers, both amorphous and semi-crystalline. In particular, with thermoplastic fibre-reinforced materials containing short glass fibres (e.g. PA66-GF30), tensile strengths of up to 90% of the base material have been achieved (Fig. 4). Especially in aerospace, this success could make a significant contribution to further weight reduction of the next aircraft generation, since the weld efficiency factor plays a decisive role in component dimensioning.

Since complex structures cannot easily be realised with wood, the combination of polymer injection moulding and wood in the advanced material mix can fully exploit its lightweight advantages. Wood provides the structure, the polymer forms complex attachments and fastening points, precisely positioned, while PSW creates the high-strength joint. As PSW does not require any additional substances, the use of bio-based or biocompatible polymers could enable composting at the end of the component’s life, thereby closing the cycle.

Tool: plug-and-play instead of special equipment

The core of the royos process is a tool head with integrated temperature control. This can easily be mounted on CNC machines or robots with a milling spindle (Fig. 5). There is no need to purchase expensive special equipment, as the welding head can be used in a wide variety of existing systems. For this purpose, the tool is supplied with the appropriate tool holder for the machine.

Operation of the system is intuitive via the control unit, where material combination and thickness are selected on a touch screen display. The required welding parameters, such as feed rate, penetration depth and dwell time at the starting point, are stored in a matrix and can be entered by the machine operator into the machine tool. A trained cutting machine operator can therefore use the PSW process immediately, without the need for special training as required, for example, for friction stir welding. Right from the development stage of the tool, particular attention was paid to simple application and practical suitability. By making use of existing equipment, new potential can be unlocked without high investment costs.

Environmental balance: circular economy instead of composite waste

Each kilogram of primary aluminium causes around 13 kg of CO₂ in extraction and processing, while glass fibre reinforced PA6 emits only about 4 kg. In the production of water-carrying electronic coolers, aluminium sheets and aluminium die-cast housings are often inseparably welded together. When the scrap is remelted, depending on the weight fractions, this leads to dilution of the alloy and thus downcycling. By substituting metals with thermoplastic polymers, the CO₂ footprint of the components is already reduced in the material supply chain. Bonded assemblies, on the other hand, usually end up in thermal recycling, since adhesive residues can hardly be removed without leaving traces. A decisive advantage of PSW becomes apparent at the end of the component’s life: PSW seams can be mechanically separated, metal scrap can be recycled by alloy type, and the polymer can be regranulated to a high degree, since no contamination takes place.

Literature

[1] Schneider, A. (2022): Darum ist Aluminium nicht gut für die Umwelt, URL: https://www.quarks.de/umwelt/muell/darum-ist-aluminium-nicht-gut-fuer-die-umwelt [Accessed on 07 August 2025].

[2] Heyner, D.; Piazza, G.; Beeh, E.; Seidel, G.; et al.: Crashtest einer Fahrzeugtür mit holzbasiertem funktionsintegriertem Türaufprallträger unter realitätsnahen Randbedingungen. In: VDI-Berichte 2387, S. 19/34. VDI Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf 2022.

Authors and contact

Mario Leitner, mario.leitner@royos.at, Cornelia Leitner, cornelia.leitner@royos.at und DI Dr. Andreas Hausberger, andreas.hausberger@royos.at,

royos joining solutions GmbH

Schlagworte

Circular EconomyHybrid CompositesHybrid WeldingPolymerPolymere Stir WeldingPolymersSustainabilityThermoplasticThermoplastics

![Joining Plastics [EN]](/images/frontend/journals/joining-plastics_sm.png)