In this article, investigations about joining with nickel nanoparticles are presented. Compared to the corresponding bulk material, nanoscale particles have a lower melting and sintering temperature. This offers great potential for joining processes at comparatively low temperatures, which can represent an alternative to conventional brazing. Elements, such as boron or silicon, that are used as melting point depressants in common solders and brazes are not needed here. This also prevents the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds in the joint seam. The joining process with nanoparticles is conducted while a pressure is applied on the joining zone with simultaneous heating under vacuum ("nanojoining"), which is similar to diffusion welding processes from a technological point of view.

In contrast to this, however, with nanojoining the holding times are significantly shorter (in the range of a few minutes). Further, the nanoparticles or more precisely, the pastes made from them (“nanopastes”) are used as a filler metal in nanojoining. The nanopastes are made from organic compounds and the nickel nanoparticles by ultrasonic-assisted dispersion. Joining tests on nickel superalloys were evaluated with regard to both, the microstructure and the shear strength of the joints.

1 Introduction and motivation

Nickel-based superalloys exhibit excellent fatigue and creep resistance at high temperatures as well as superior oxidation resistance, which qualifies them for use in power generation technology and aerospace applications, particularly in turbine construction [1]. In many design concepts, there is a need to join these materials reliably, often achieved through brazing. However, in state-of-the-art brazing using nickel-based brazes with boron and silicon as melting point depressants, the strength is diminished due to brittle intermetallic precipitates (borides and silicides) in both the brazing seam and the diffusion zone of the base materials [2; 3].

A solution to avoid the brittle intermetallics is to employ diffusion brazing, but its long holding times can lead to other undesirable microstructural changes, negatively affecting mechanical properties as well [4; 5]. Furthermore, for some materials in turbine construction joining temperatures below 1100 °C are desired which is hard to achieve with conventional brazes if properties such as high temperature strength and oxidation resistance should be maintained. In this context, nanojoining offers a promising alternative.

Nanoscale materials exhibit reduced melting and sintering temperatures, compared to their corresponding bulk material. But after carrying out the joining process they regain properties of the bulk. The presented work demonstrates that joining of nickel based superalloys is possible at only 675 °C by using nickel nanoparticles while achieving a shear strengths of more than 100 MPa. With optimized parameters, shear strengths of up to 218.7 MPa are possible. Joining with nickel nanoparticles thus enables low joining temperatures while maintaining high service temperatures, making this method an interesting alternative to conventional brazing processes. Additionally, the reduced temperatures offer potential for energy savings.

2 Basics of nanojoining

The reduction in the melting (and sintering) temperature of nanoparticles is due to their high surface-to-volume ratio. As a result, the surface atoms predominantly determine the properties of nanoscale materials. Surface atoms are not coordinatively saturated, so not fully surrounded by neighbour atoms, leading to significantly reduced binding energy. This lowers the thermal energy required to overcome the solid state, causing nanoparticles to have a reduced melting and sintering temperature compared to their bulk material counterpart [6; 7]. This effect can be used for a joining process where the nanoparticles sinter [8], ideally forming a fully densified joint seam. Since the effect of reduced melting and sintering temperatures vanishes as the particles coalesce, the joint seam exhibits the properties of the bulk material after the joining process. This allows for joining at relatively low temperatures while still achieving joints with high temperature resistance and strength.

Previous studies have primarily investigated nanoparticle-based joining as an alternative to soldering in power and microelectronics, using silver nanoparticles [9...13] and copper nanoparticles [14...16]. Based on this, nanojoining has increasingly become a focus of research for high-performance joining in recent years. Studies have investigated the joining of steels and nickel alloys using silver nanoparticles [17; 18]. Additionally, joining with nickel nanoparticles, which provide significantly higher temperature resistance after joining compared to silver material, has also been investigated for joining steels [19; 20] and Ni base alloys [21...24].

To utilize nanoparticles for joining applications, they must be processed into a suspension, such as a paste. These so-called nanopastes consist not only of nanoparticles (in this case nickel nanoparticles, abbreviated as "Ni-NP") but also include solvents and stabilizers, so organic components. After application to the base material and subsequent pre-drying, these nanopastes can be used in a pressure-assisted joining process to create structurally durable joints.

3 Nanoparticles and organics for paste preparation and base materials

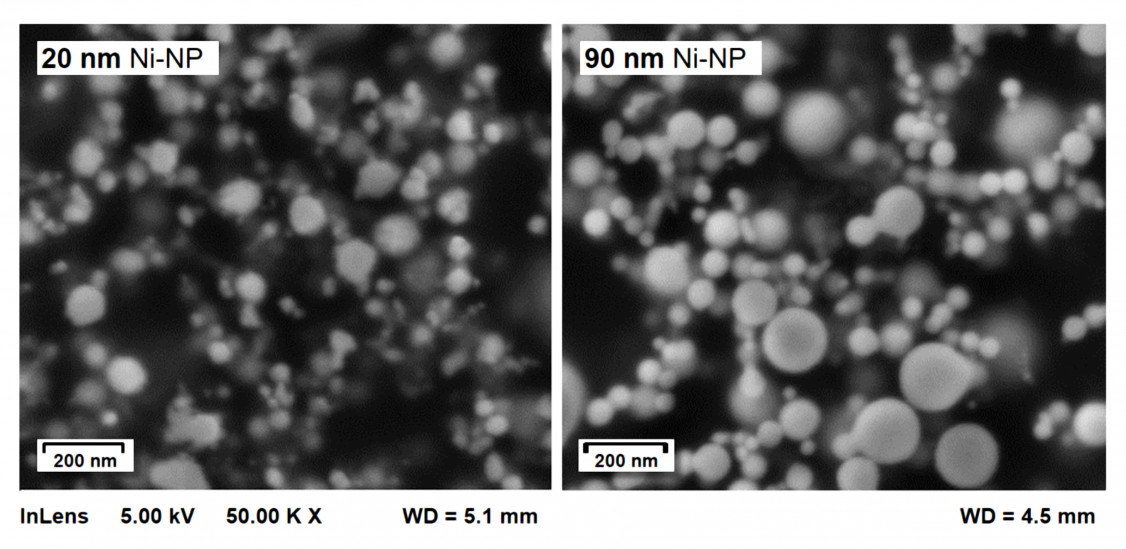

For the experimental work here, Ni-NP were used with two different mean diameters to prepare nanopastes. According to the manufacturer, the average particle sizes are 20 nm and 90 nm, which was confirmed mainly through in-house SEM imaging, as shown in Fig. 1.

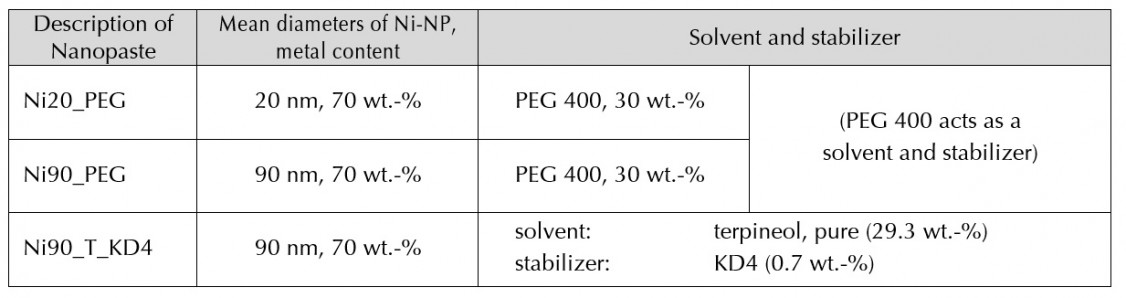

Based on experience in this field and a previous literature review, promising chemical systems were assorted for the preparation of the nanopastes. Through preliminary tests on solvent volatility, maximum achievable metal content, thermal behavior and other factors, three promising nanopastes were ultimately selected [25...27]. Their compositions are listed in Table 1.

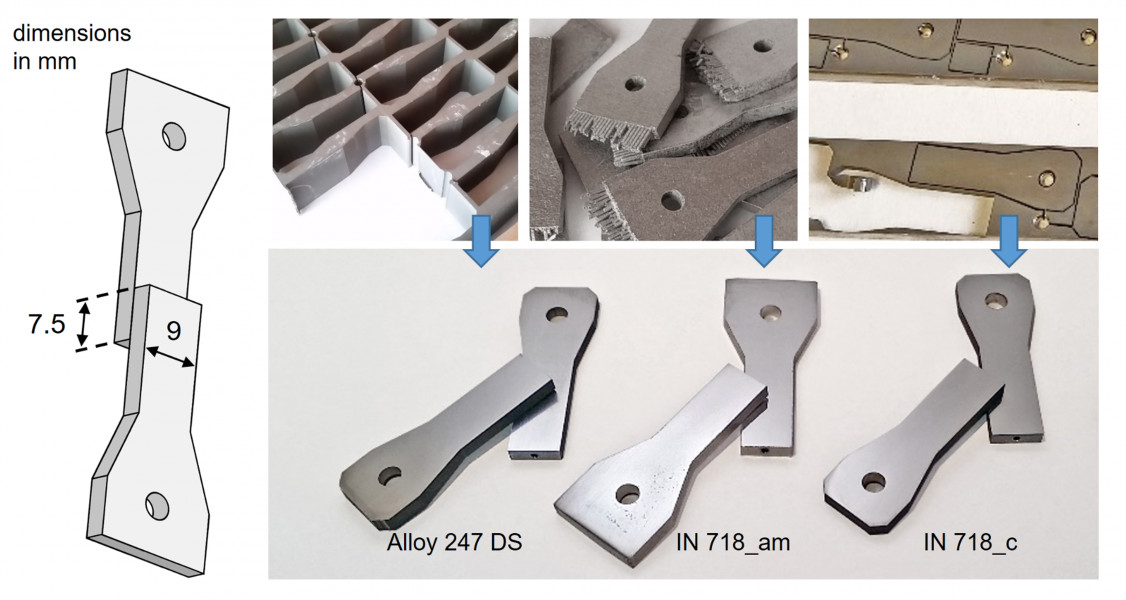

Two of the pastes consist of only Ni-NP and PEG 400, with the only difference between them being the size of the Ni-NP used. PEG 400 is a macromolecular substance that simultaneously acts as solvent and stabilizer. The third paste is a mixture of 90-nm Ni-NP, pure terpineol (solvent), and the stabilizer Hypermer KD4. To prepare the pastes, the components of each paste were precisely weighed on a laboratory scale and sequentially added to an appropriate vial. All ingredients were then intensively mixed using pulsed ultrasound (24 kHz). The sonotrode was in direct contact with the paste, dispersing it until sufficient homogeneity was achieved (5 cycles of 1 minute). The temperature was maintained at room temperature using a water bath. The joining tests were conducted on different Ni base materials: Alloy 247 DS (DS: directionally solidified), additively manufactured Inconel 718 (abbreviated as IN 718_am) and conventionally casted Inconel 718 (abbreviated as IN 718_c). From these base materials, parts were machined with a 9 mm wide end on one side. In case of IN 718_am, the individual parts were delivered as near net shape. Two of these parts were used for the joining process to obtain a shear test sample with an overlap length of 7.5 mm (joining area 67.5 mm²).

Fig. 2 illustrates the sample geometry as well as the different supply forms of the base materials. A uniform surface was prepared on all test specimens by wet grinding on an automatic driven SiC paper pad with a grit size of 600.

4 Application of nanopastes and joining process

The Ni nanopastes were applied as a 50 µm layer on the overlap area of the samples using a simple peel-off technique on a device providing a 50 µm gap. This was done for each sample part whereas two of these parts form a complete joining sample. It should be noted that the total paste application of 100 µm does not represent the final joining seam thickness. The actual thickness is decreased due to pre-drying the paste and the densification during the joining process, mainly driven by the applied joining pressure. A final thickness of approximately 10 to 20 µm can be seen in the section of the microstructural characterization. A pre-drying of the paste layer was performed before the joining process to prevent uncontrolled displacement of the paste during the pressure-assisted process and to remove some of the organic content. This was achieved by simply heating the samples on a laboratory hotplate. The temperature and duration has a significant impact on the final joining results. Various pre-drying conditions were preliminarily tested for the individual paste compositions. Based on that, the following parameters were used: 90 seconds at 200 °C for PEG-based pastes and 90 seconds at 140 °C for terpineol-based pastes.

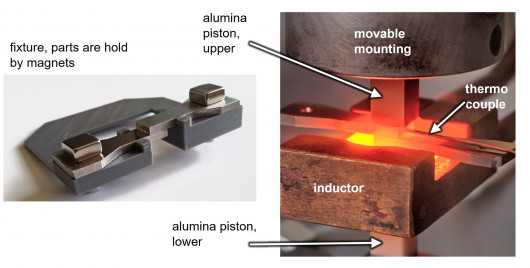

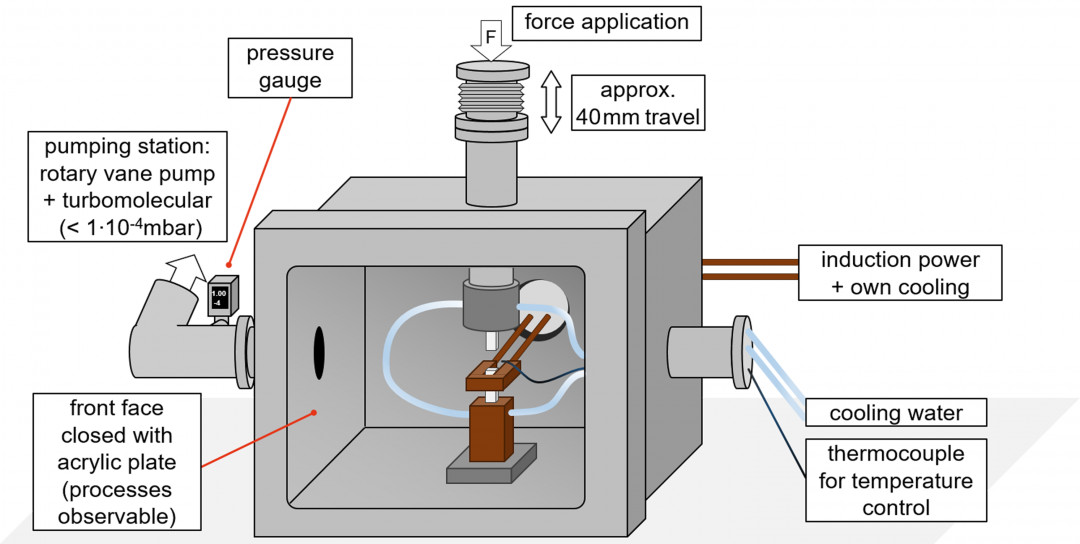

For the joining process, two individual parts of a base material, each coated with a layer of pre-dried nanopaste, were placed in a specialized fixture. The sample arrangement was then inserted into the chamber which is able to operate under high vacuum at pressures below 4 × 10⁻⁴ mbar to avoid any adverse effects from air during the joining process. Holders made of Al₂O₃, one of which axially movable to apply pressure on the sample’s overlapping section from the outside, keep the sample in a fixed position so that the fixture can be removed before joining. On the end of one sample is a drill hole, into which a thermocouple is inserted to control the process temperature. After generating vacuum, the sample material was heated inductively at a heating rate of 150 K/min up to the specified temperature, according to the design of experiments (Table 2). After the holding time ended, the sample cooled down freely. The whole experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3 and 4.

5 Design of Experiments (DOE) for nanojoining tests

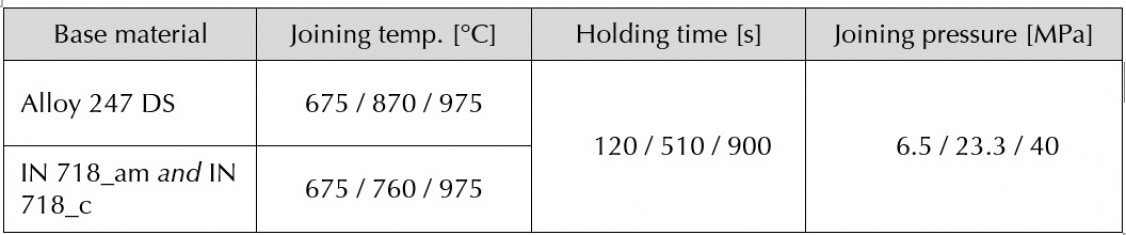

The experimental work should reveal the influence of joining parameters on the achievable bonding strengths of the investigated base material-nanopaste combinations. Since nanojoining is a thermal bonding process like brazing and other methods, temperature and holding time are essential factors. It is also known from experience that joining pressure plays a significant role in nanojoining. These three parameters were considered as input variables in a statistically optimized DOE and are varied in three increments (minimum, medium and maximum value). The associated limits for these parameters, shown in Table 2, are based on preliminary tests and cover a wide range of process parameter variation. For each parameter set, 2 to 3 repeating samples were produced. This DOE is used for every combination of the three different nanopastes and base materials, so for 9 combinations in total.

6 Results and evaluation of the joining tests – joint microstructure

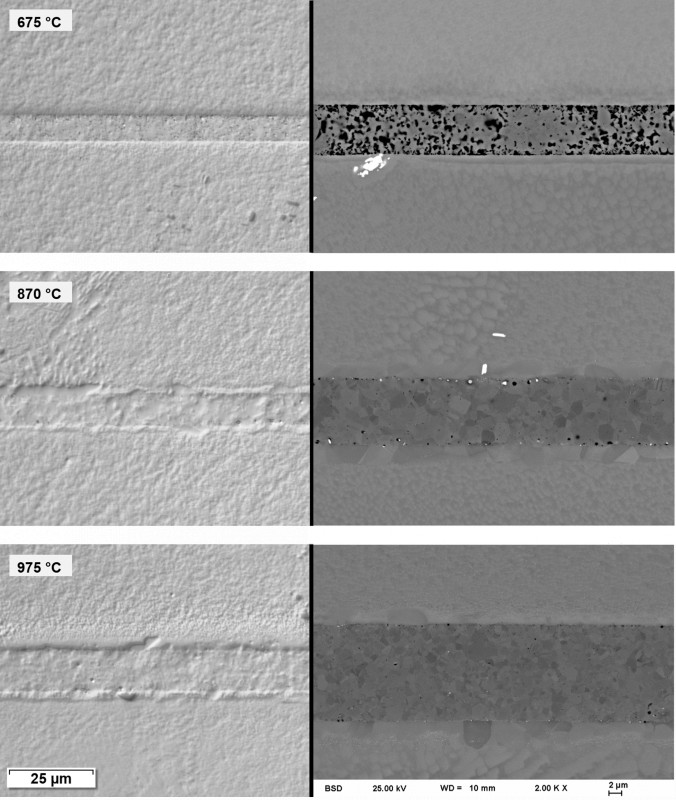

The microstructure of the joining zones was analyzed through bright-field microscopy, differential interference contrast microscopy (DICM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Depending on the base material-paste combination and the joining parameters, the joints show varying degrees of porosity, defect density and adhesion to the base material. For joining parameters in the lower range, more of these defects are present. This is especially evident in the SEM image, Fig. 5, top right (joining temperature of 675 °C), whereas the same structure of depressions and pores appears mostly bright in the DICM image (top left). For top end parameter values, particularly at high bonding temperatures, defects occur less up to almost non-existent.

Fig. 5 contains light microscopy (DICM) and SEM images of further Alloy 247 DS samples joined with paste Ni90_PEG. All were produced with a holding time of 510 seconds (8.5 minutes) and a joining pressure of 23.3 MPa, with only the joining temperature varied between 675 °C, 870 °C and 975 °C. The images reveal recrystallization in the base material at the joint seam interface, which could be at-tributed to an increased Ni concentration due to diff usion of Ni from the seam into the base material. The higher Ni content leads to a decrease of the recrystallization temperature decreases in the areas of the base material close to the joining seam.

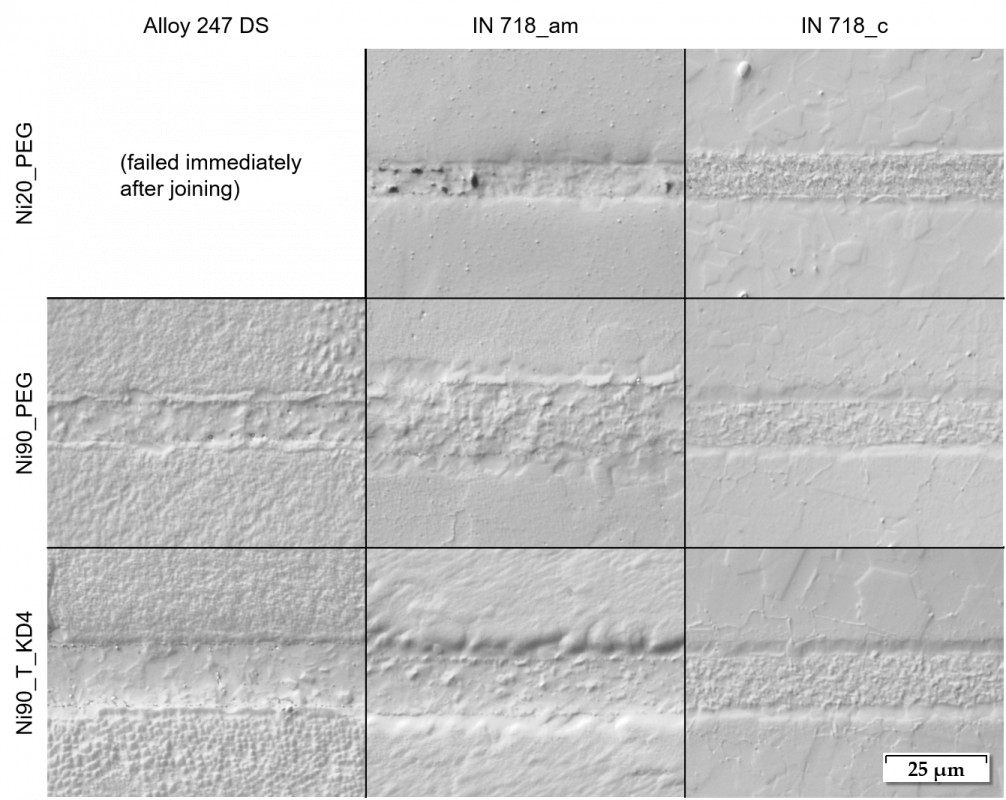

Fig. 6 shows light microscopy images (DICM) for all 9 base material-paste combinations at a uniform joining temperature of 870 °C. Holding time and joining pressure are also constant in this comparison at values of 510 seconds (8.5 minutes) and 23.3 MPa. Depending on the base material and the nanopaste used, certain differences in the microstructure are visible. When comparing the joining seams of the nanopastes with 20 nm and 90 nm Ni-NP, paste Ni20_PEG (top row) results in more defects and also shows more inclusions, as illustrated in greater detail in Fig. 7.

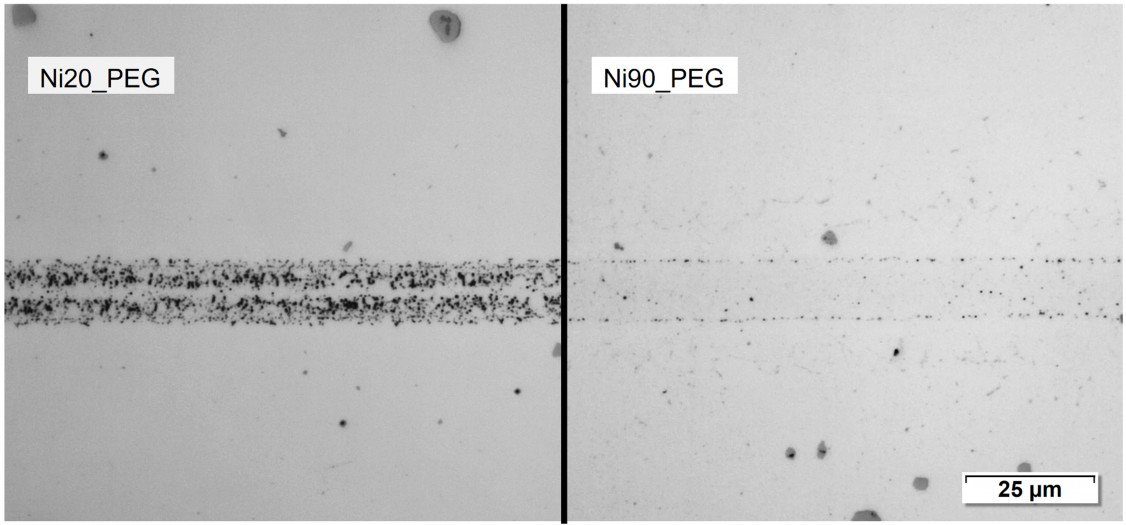

For the two other pastes, Ni90_PEG and Ni90_T_KD4, dense joining seams with good bonding to each of the investigated base materials ca n already be achieved in this medium joining parameter range. The differing seam formation of the pastes Ni20_PEG and Ni90_PEG, whose compositions are identical except for the size of Ni-NP used, is directly compared in Fig. 7. Both samples were joined at 975 °C with a holding time of 510 seconds (8.5 minutes) and a joining pressure of 23.3 MPa. For the Ni20_PEG paste, significantly higher porosity, as well as inclusions and residues of organic material, can be observed under identical joining conditions. Even for other samples with near optimal joining parameters, both the microstructure of the seam are consistently more defective than in the case of the paste containing 90-nm Ni nanoparticles. This initially appears counterintuitive, as theoretical behavior of nanoscale particles suggests that smaller particles should sinter at less thermal energy (lower temperatures, shorter holding times) and thus form a joint more easily than larger ones. However, one potential ex-planation could be the differing oxidation tendencies of the particles. It can be assumed that Ni nanoparticles, similar to bulk nickel, form an oxide layer when exposed to air. The oxide layer might be more pronounced for the 20-nm particles due to their higher reactivity compared to larger particles. Additionally, their specific surface area is significantly greater, which increases the overall amount of ox-ide. As a result, more oxide is introduced into the seam, making it more diffi cult to form a bonding between both the particles to each other and to the base material.

7 Results and evaluation of the joining tests – joining strength

The mechanical strength of the joined samples was determined by shear testing. The samples were clamped at their head section in a testing machine (Zwick Allround-Line 20 kN) using a vice. This clamping allows compensation for the vertical off set of both samples ends, given by the overlap geometry. The test was carried out at a quasi-static shear rate of 10-3/s, which corresponds to a travel speed of 0.0075 mm/s for an overlap length of 7.5 mm. The pre-load for each sample was 100 N. The test was then continued until the sample broke, while the force and the machine travel distance were recorded.

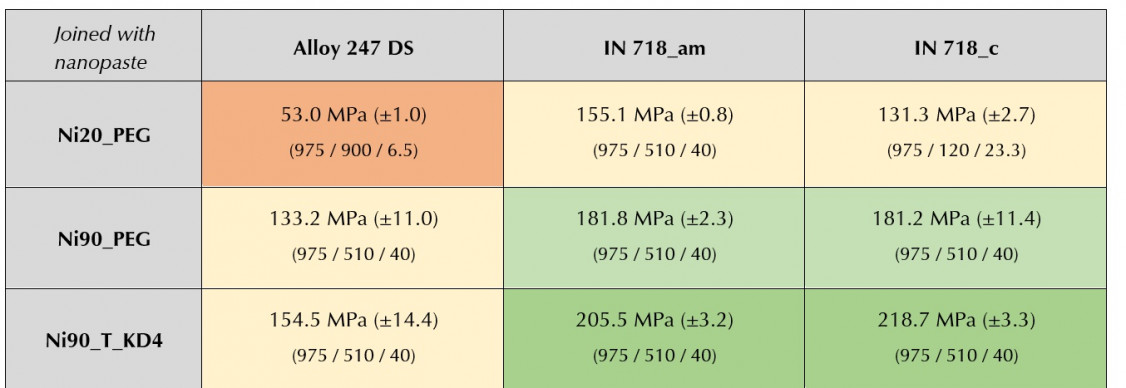

After testing all joining samples, Table 3 lists the maximum achieved strengths for each base material-paste combination along with the corresponding parameter set. In this comparison, the joining samples with Alloy 247 DS as base material exhibit the lowest values. Samples made from IN 718_am and IN 718_c are at a higher strength level for all pastes and across all joining parameters.

Visual observation of the seams of Alloy 247 DS does indicate, that the adhesion is slightly more defective compared to the other two base materials, but only for some joining parameter sets. This drop in overall joining strength is probably due to the content of the γ’ phase, which is significantly higher for Alloy 24 DS with a volume fraction of 62 % [28]. In comparison, the Inconel 718 material exhibit approximately 22 % [29]. It is likely that the nickel formed from the nanopaste adheres less strongly to γ’ phase areas as this is an intermetallic phase and lacks of a purely metallic character. So bonding to the base material’s nickel solid solution is stronger. This means that the joining strength is impaired when a high γ’ content is present in the base material, as is the case with Alloy 247 DS.

The nanopaste itself has also a significant influence on the shear strength. When using the Ni20_PEG paste (20-nm particles), the shear strengths were lower across all base materials compared to Ni90_PEG (90-nm particles). This can be correlated with the microstructure appearance, as described in the corresponding section. Furthermore, within the pastes containing 90-nm Ni-NP, terpineol as solvent and KD4 as stabilizer (Ni90_T_KD4) lead to higher shear strengths for every base material compared to the paste based on PEG.

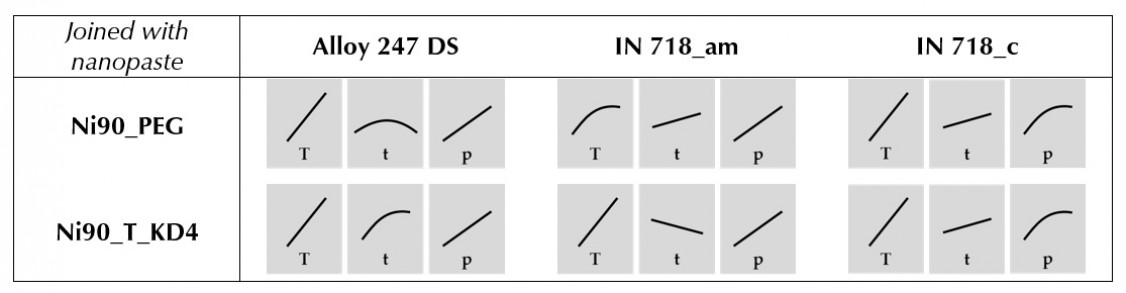

The evaluation of the shear tensile tests also provides insights on the influence of the joining parameters. Only six of the nine base material-paste combinations could be analyzed in more detail, as too many joining samples from the three series using the Ni20_PEG paste (20-nm particles) failed under minimal force application, so no suitable database was generated. Based on the processable data, models were created for each base material-paste combination, incorporating the three joining parameters as input variables to determine their influence on the measured shear strength. To break down the data for the presentation here, the observed dependencies are provided as qualitative trends in Table 4.

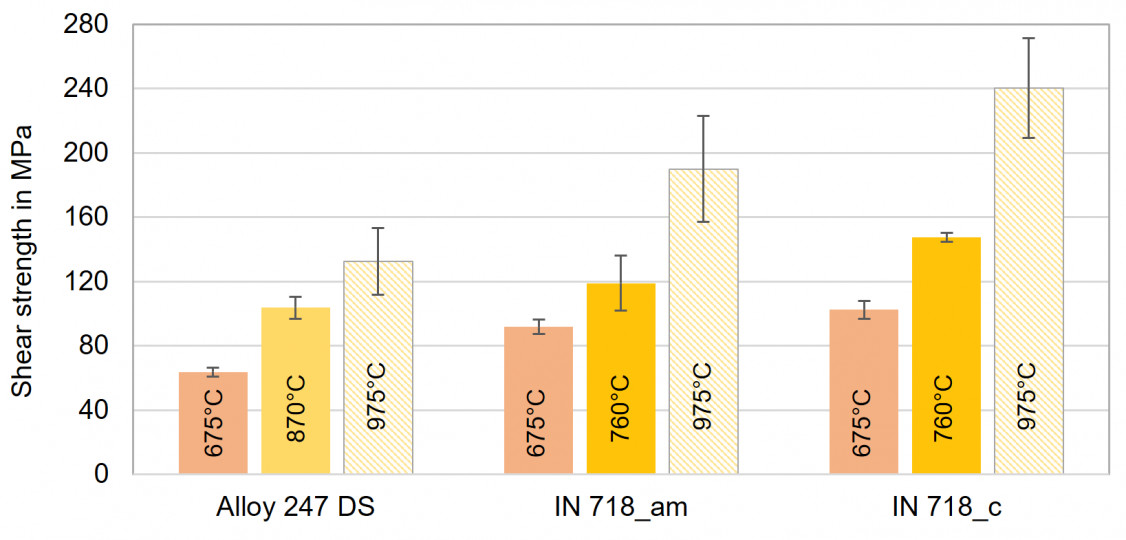

Future research will focus on improving the bonding to the base material. For example, pretreatment of the base materials could be explored to enhance diffusion between the base material and the joint seam at lower temperatures, or the use of fluoride-ion-cleaning (FIC), which is commonly employed in turbine repair of nickel alloys. Additionally, to facilitate practical application of the process, efforts will be made to identify methods for reducing or entirely eliminating the joining pressure while maintaining the desired joint properties. It is evident that, regardless of the base material and paste, a high joining temperature always leads to the highest bonding strengths. There is a rapid increase in the shear tensile strength in the range investigated (675 °C to 975 °C). Fig. 8 shows achieved shear strengths at different joining temperatures, derived from samples that were joined with the most promising paste (Ni90_T_KD4) with a holding time of 15 min and a joining pressure of 23.3 MPa.

The outcome for some parameter sets was modeled for this plot (hatched bars), because due to the statistically optimized DOE, experimental data is only available for certain parameter sets. For the joining pressure, it also applies that the highest values consistently lead to higher strengths of the joint sam-ples. However, the influence on the shear strength is a bit more diverse. For IN 718_c, high joining pressures only lead to a slight increase in the shear strength and finally hit a plateau, see Table 4. Overall, the influence of joining temperature and pressure is as expected.

The holding time as the third main process parameter shows initially a weakly positive influence on the shear strength in four of six base material-paste combinations, as shown in Table 4. In one case, a plateau formation is observed (Alloy 247 DS + Ni90_T_KD4). The other two combinations exhibit a rather unusual behavior. For Alloy 247 DS + Ni90_PEG, the maximum shear strength occurs at a medium holding time of approximately 9 minutes, while shorter or longer holding times result in a decrease in strength. In the case of IN 718_am + Ni90_T_KD4, a negative tendency is observed, meaning shorter holding times sometimes lead to higher shear strengths, which was confirmed upon examining individual results of specific parameter sets. This is therefore not an effect of random result scattering. Microstructural images of the respective samples show no significant abnormalities in comparison. At this point, only a hypothesis can be provided. The unexpected behavior could be caused by depletion of alloying elements in the base material near the joint seam, which diffuse into the joint seam. The depletion of alloying elements in this area could lead to a weakening of the material. For more precise conclusions, further investigations are required and other explanations are also conceivable.

8 Conclusions and outlook

This study extensively investigated the joining of various nickel-base alloys using nickel nanopastes. For this, various nickel nanoparticle-containing pastes were prepared and used in comprehensive joining experiments with three different base materials. With an appropriate choice of joining parameters, the microstructure of the joints appears almost defect-free under vacuum processing, regardless of the base material. At lower temperatures or when using the paste with 20 nm Ni nanoparticles, both porosity and number of bonding defects are increased. However, even at the lowest joining temperature investigated (675 °C), shear strengths exceeding 100 MPa can still be achieved when using conventionally manufactured IN 718. Overall, it was demonstrated that various nickel-base materials can be effectively joined with Ni nanopastes at relatively low temperatures. Shear strengths significantly increase with higher joining temperatures and pressures. The maximum shear strength observed in this series of experiments was 218.7 MPa for the base material Inconel 718 (conven-tional). Furthermore, it was unexpectedly found that the nanopastes with 90 nm Ni nanoparticles yield better joining results than the paste with 20 nm particles. Rea-sons for this were discussed.

Future research will focus on improving the bonding to the base material. For example, pretreatment of the base materials could be explored to enhance diffusion between the base material and the joint seam at lower temperatures, or the use of fluoride-ion-cleaning (FIC), which is commonly employed in turbine repair of nickel alloys. Additionally, to facilitate practical application of the process, efforts will be made to identify methods for reducing or entirely eliminating the joining pressure while maintaining the desired joint properties.

(Source: Benjamin Satler, Susann Hausner, Guntram Wagner, Chemnitz University of Technology)

References

[1] Bürgel, R., H. J. Maier, T. Niendorf: Handbuch Hochtemperatur-Werkstofftechnik: Grundlagen, Werkstoffbeanspruchungen, Hochtemperaturlegierungen und -beschichtungen. Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011.

[2] Heinz, P.: Diffusionslöten von einkristallinen Nickelbasis-Superlegierungen mit binären Nickel-Germanium-Lotwerkstoffen. Diss., Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg 2009.

[3] Wikstrom, N. P., O. A. Ojo, M. C. Chaturvedi: Influence of process parameters on microstructure of transient liquid phase bonded Inconel 738LC superalloy with Amdry DF-3 interlayer. Materials Science and Engineering: A, Vol. 417 (2006), Nr. 1-2, pp. 299/306.

[4] Steuer, S.: Diffusionslöten von Mischverbindungen aus ein- und stängelkristallinen Nickelbasis-Superlegierungen: Ausscheidungsvorgänge in den Grundmaterialien Diss., Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg 2012.

[5] Blank, R., et al.: Prozessentwicklung zum Hochtemperaturlöten der artfremden Werkstoffkombination INCONEL 625 – 16Mo3 für die Anwendung an Gasturbinenbrennerkomponenten. Werkstoffe und Werkstofftechnische Anwendungen 72 (2018), pp. 158/67.

[6] Dittmeyer, R., K. Winnacker, L. Küchler: Chemische Technik: Prozesse und Produkte. Band 2: Neue Technologien. Kapitel 9: Nanomaterialien und Nanotechnologie. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2003.

[7] Rössler, A., G. Skillas, S. E. Pratsinis: Maßgeschneiderte Werkstoffe. Nanopartikel-Materialien der Zukunft. Chemie in unserer Zeit 35 (2001), pp. 32/41.

[8] Akada, Y., et al.: Interfacial Bonding Mechanism Using Silver Metallo-Organic Nanoparticles to Bulk Metals and Observation of Sintering Behavior. Materials Transactions 49 (2008) 1537-1545.

[9] Siow, K. S., Y. T. Lin: Identifying the Development State of Sintered Silver (Ag) as Bonding Material in Microelectronic Packaging via A Patent Landscape Study. Journal of Electronic Packaging, Transactions of the ASME. 138 (2016) 037001.

[10] Zhang, H., et al.: Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using large-area arc discharge and its application in electronic packaging. Journal of Materials Science 52 (2017), pp. 3375-3387.

[11] Peng, P., et.al.: Joining of Silver Nanomaterials at Low Temperatures: Processes, Properties, and Applications. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 7 (2015). pp. 12597-12618.

[12] O’Neal, C.B., et al.: Advanced Materials for High Temperature, High Performance, Wide Bandgap Power Modules. Journal of Electronic Materials 45 (2016), pp. 245–254.

[13] Watanabe, T. et al.: Thermal Stability and Characteristic Properties of Pressureless Sintered Ag Layers Formed with Ag Nanoparticles for Power Device Applications. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 31 (2020), pp. 17173-17182.

[14] Del Carro, L., et al.: Oxide-Free Copper Pastes for the Attachment of Large-Area Power Devices. Journal of Electronic Materials 48 (2019), pp. 6823-6834.

[15] Zhang, B., et al.: In-air sintering of copper nanoparticle paste with pressure-assistance for die attachment in high power electronics. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 32 (2021), pp. 4544-4555.

[16] Liu, X., et al.: Microstructural evolution, fracture behavior and bonding mechanisms study of copper sintering on bare DBC substrate for SiC power electronics packaging. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 19 (2022), pp. 1407-1421.

[17] Hu, A. et al.: Nanobrazing for Turbine Blade and Vane Repair. Adv. Mater. Process 175 (2017), pp. 25-29.

[18] Hausner, S., M.F.-X., G. Wagner: Microstructural Ivestigations of Low Temperature Joining of Q&P Steels Using Ag Nanoparticles in Combination with Sn and SnAg as Activating Material. Applied Sciences 9 (2019) 539.

[19] Hausner, S., S. Weis, G. Wagner: Joining of steels at low temperatures by Ni nanoparticles. DVS-Reports 325 (2016), pp. 278-284.

[20] Eluri, P., B. Paul: Hermetic joining of 316L stainless steel using a patterned nickel nanoparticle interlayer. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 14 (2012), pp. 471-477.

[21] Wang, J. et al.: Diffusion kinetics of transient liquid phase bonding of Ni-based superalloy with Ni nanoparticles: A molecular dynamics perspective. Computational Materials Science 152 (2018), pp. 228-235.

[22] Bridges, D., R. Xu, A. Hu: Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ni nanoparticle-bonded Inconel 718. Materials and Design 174 (2019) 107784.

[23] Awayes, J., I. Reinkensmeier, G. Wagner, S. Hausner: Nanojoining with Ni Nanoparticles for Turbine Applications. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 30 (2021), pp. 3178-3186.

[24] Bridges, D., et al.: Wettability, Diffusion Behaviors, and Modeling of Ni Nanoparticles and Nanowires in Brazing Inconel 718. Advanced Engineering Materials 23 (2021) 2001053.

[25] Sattler, B., S. Hausner, G. Wagner: Investigation of Shear Strength and Microstructure Formation of Joined Ni Superalloys Using Ni Nanopastes. In: Nanomaterials 12 (2022), 18.

[26] Sattler, B., S. Hausner, G. Wagner: Feasibility, processing properties and thermal behavior of Ni nanopastes produced by ultrasound-enhanced dispersing. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 1147(2021), Nr. 1, 12011.

[27] Sattler, B., S. Hausner, G. Wagner: Properties of Ni nanopastes for structural joining as an alternative to conventional braze fillers. DVS-Reports, Vol. 381, pp. 44/49. DVS Media, Düsseldorf 2022.

[28] Basak, A., S. Das: Carbide formation in Nickel-base superalloy MAR-M247 processed through scanning laser epitaxy (SLE). Proc. “International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium 2016”, pp. 460-468.

[29] You, X., et al.: Effect of solution heat treatment on the precipitation behavior and strengthening mechanisms of electron beam smelted Inconel 718 superalloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A 689 (2017), pp. 257-268.

Schlagworte

ADAlloysBrazingDINJoiningMaterialMaterialsMetalMIGNickelResearchSolderingStudyTechnologyTIGWelding